In Pursuit of Responsible Design

Exploring regional textile sourcing, longevity, and zero waste design with Fibershed Design Challenge

For this month’s issue, I zoomed in on thoughts around my participation in Fibershed’s “Borrowed from the Soil” Design Challenge. Fibershed, a non-profit organization that focuses on regional fiber systems, creates this year-long challenge that runs from March 2023 to February 2024.

I signed up on the very first day this challenge was announced, and I was elated to get my participation acceptance email a few days later. You see, I have been a fan of Fibershed for a few years now. Learning about sustainability in textiles and regenerative agriculture quickly led me to Fibershed’s abundant resources. This is an organization that constantly champions sustainability of materials (via natural soil-to-soil fiber systems) AND community health. Having the opportunity to be closer to this wonderful organization and other textile artists through this challenge feels very special.

So, let’s get to the topics of this month:

What is Borrowed from the Soil Design Challenge?

Getting exposed to regional textile sourcing

Pondering what “designing for longevity” means

Warming up for zero waste design

What is “Borrowed from the Soil” Design Challenge?

In a nutshell, it is Fibershed’s invitation to textile designers in Northern and Central California to envision a soil-to-soil system for our material culture - the whole process of growing natural fibers (like cotton and wool), harvesting and processing locally grown materials, responsibly making them into products, and returning them into the soil as compost at the end of their lifecycle.

This is a radical vision, considering that our global textile system is reliant on exploitative petroleum-based practices. While awareness of soil-to-soil circularity is rising in this climate emergency era, building the necessary infrastructures to bring this concept up to scale is still very much an uphill climb.

Participating textile designers are encouraged to “explore beyond the product, connecting your process and products with the farmers, the people, and the land in our region; while also looking at how your design choices can embed longevity, compostability, and respect for the soil.“

We get to participate in “a variety of educational events, resources & farm tours to build our collective understanding of the interconnectedness between material and design choices, and the land and people whom these choices impact. All of which will culminate in a Fall gallery showing and final Spring 2024 showcase.”

*All quoted phrases are cited from the Fibershed Design Challenge web page.

During the design challenge launch event in April, most participants met up for the first time at Fibershed Learning Center in Point Reyes Station. After a day full of introductions, rotating workshops, and beautiful scenery, I went home inspired and started thinking about a prototype design that touches on at least one of the following aspects: regional textile sourcing, designing for longevity, and zero waste design.

Regional textile sourcing

This technical focus of regional textile sourcing is what excites me the most about the year-long challenge. It gives access to independent textile artists like myself to regionally produced natural fibers, such as wool harvested from McCormack Ranch in Rio Vista, whose ranch tour I joined last month. Such wool eventually makes its way to shops like Lani’s Lana, which sells exquisite fabrics to create with.

It makes me aware of organizations like California Cotton & Climate Coalition! Designers involved in Fibershed Design Challenge are amongst the first in the world to have access to C4’s first harvested cotton (in 2021), spun in North Carolina (Hill Spinning - Thomasville, NC), 30/1 carded, ring spun yarn made from Phytogen 764 fiber, manufactured by Laguna Enviro Fabrics in Los Angeles (textile mill).

Moreover, C4 makes me think about a concept of product design timeline with a farmer in mind. For example, invest in farmers to buy cotton seeds that will be ready for textile production 20 months after. Designing with the regional ecosystem in mind requires flexibility, and it is a big departure from the go-to starting point of purchasing fabrics by the bolts or yards. I find it very energizing and humane.

-

What’s not humane is knowing that wool is deemed much less sustainable than polyester according to Higg MSI (Material Sustainability Index).The index bases this judgment from environmental impact alone, devoid of interconnectedness of socio-economic or cultural impact. PETA also blasts wool and urges public to use vegan “alternatives” that are essentially oil-based fabrics. These stories eventually pose a critical question: how do YOU determine sustainability as an individual?

Gaining regional textile sourcing knowledge is a new chapter to explore for me.

Many of you know I mainly use pre-owned textiles and garments. While there is no shortage of discarded textiles and samples out there, creating products this way is simply a REACTION to the overwhelming amount of textile waste produced each year. The amount of dyes and forever chemicals imbued into these materials have deteriorating repercussions to our bodies in the long term, and I won’t ever know who made these textiles or clothes.

I realize that what I’m doing right now is a band-aid effort at best, and not the sustainable revolution that we all desperately need (i.e. no more oil-derived fabrics and textiles, fair-trade compensations that are focused on farmers and garment workers’ well-being).

My aspiration is to be part of this radical vision - source textiles that are responsibly made locally, and have an ACTIVE role in supporting a healthy ecosystem and building traceable, well-funded communities of growers and textile processors.

It’s a lofty goal in the current reality, I know. However, North and Central California textile artists / makers are fortunate to have organizations like Fibershed that have done this crucial work over the years. They sponsor natural fiber growers and farmers, who are equipped with various regenerative agriculture / carbon farming techniques. These methods not only improve soil health and biological diversity in the ecosystem, but also reduce the need of synthetic chemicals in the farming practices.

Moreover, Fibershed connects them with brands, independent makers and designers to drive up demand and encourage responsible product designs. This all encourages a healthy and connected community of growers, textile makers, and consumer product designers.

“Designing around what the land gives you, and considering that as a feature instead of a bug.” - Lauren Bright, California Cotton & Climate Coalition (C4)

Designing for longevity

Whenever longevity is mentioned, we may automatically associate it with quality.

Discussing quality would be a natural extension of what I discussed last month around aesthetics, functions, and cost. Discerning quality can be subjective depending on a person’s taste and their fashion experience for sure, but a garment’s quality directly influences its longevity. Next to the fiber content and finish, how the garment (product) is constructed dictates its longevity.

But that product focus is not what the design challenge calls out for. The challenge encourages us to design a product with focus on the user. What will make them reach out for this item over and over again, long after the initial excitement wears off? What kind of feeling does it generate / what kind of specific function does it fulfill that makes the user keep wearing it? Does the design also consider future mending or alterations in mind?

Alix Vasquez of Herderin asks, “How can we interrogate, as designers, the concept of longevity in our approach to design, so that people do not just throw away a garment when their interpretation of the life cycle is done?”

This posed question makes me think about brand v. consumer paradigm, something that It’s A Working Title discusses recently. As makers, we communicate the whys and hows of our products in whichever channels we choose. However, once our products are in the hands of the customer, the whys and hows of their use may be completely different from what the makers initially intended. For garments, the sooner the disconnect happens, the faster it gets discarded.

That’s why some fast fashion items can stay with some customers for a long time despite its planned obsolescence. Or that some luxury items don’t stay in one’s wardrobe for long before it gets resold or (gasp!) discarded.

-

For this design challenge, I want to rethink my problematic connection with a specific garment: a jumpsuit. I really want to love it, I really do. But no matter how well it is made, a jumpsuit always requires you to strip down when you go to the restroom. The feeling of sudden cold air / chilliness, combined with the confined feeling in a small space have made me dislike jumpsuits very much.

Repairing my relationship with jumpsuits by hashing out functions I timelessly want, feelings I’d like to have (when I’m wearing it) in addition to aesthetic design choices and preferences would be a great practice to start with!

Exploring Zero Waste Design

For those of us who are not familiar with the zero waste design concept, I recommend watching this Zero Waste Pattern Cutting (ZWPC) video by Katie Rant.

Several critical points about ZWPC that Katie mentioned are:

Zero waste patterns use 100% of the fabrics; no scraps or leftover fabrics in the aftermath, not even clipped corners.

All pattern pieces made need to include seam allowances.

Designers need to know type of seams to do.

Knowing the width of fabric is key for accurate and successful zero waste design.

I have been exploring zero waste design in my previous makes, albeit not in a way that the above method calls for. Working with fabric remnants and cutouts usually means working with irregular shaped fabrics instead of a perfectly rectangular one.

The pink sleepwear set was my first attempt at being zero waste, with all slivers and scraps made their way into decorative ruffles. This dark green leisure wear was almost zero waste, if not for the curved cut around the ankles.

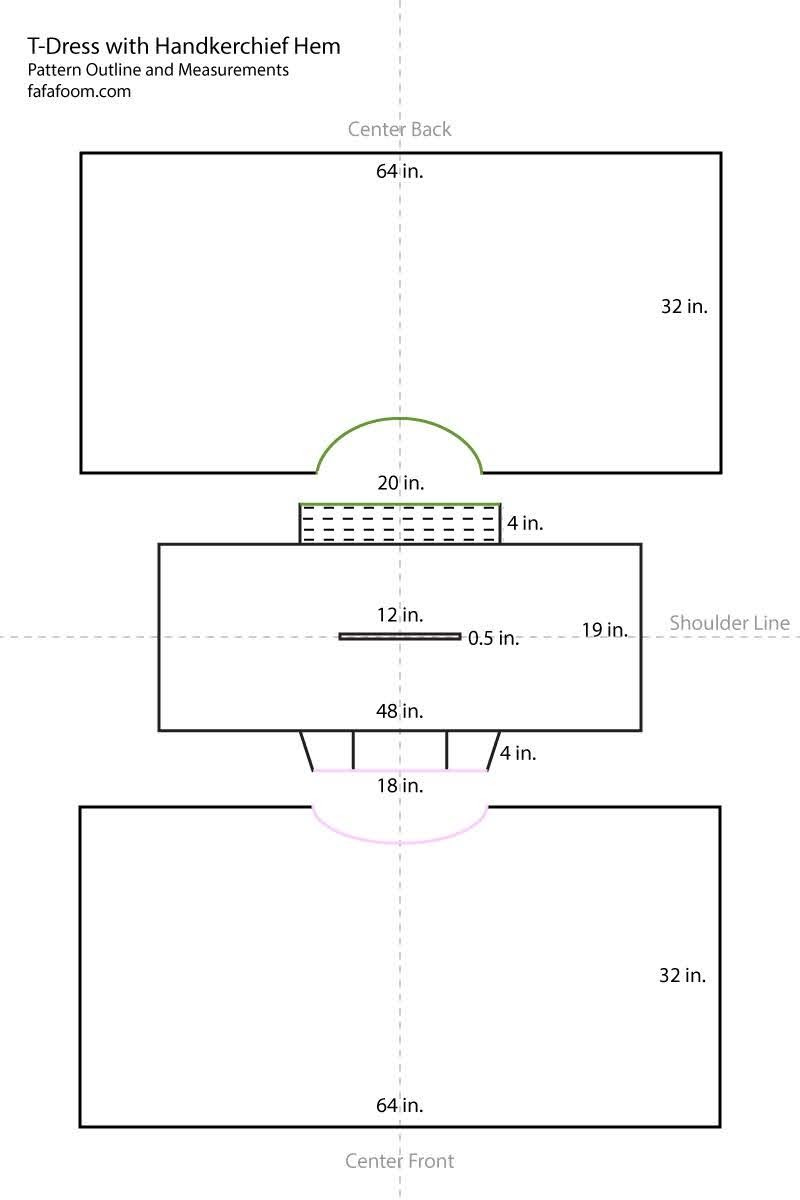

That said, I did work with rectangular shaped fabrics. In 2020, I upcycled two linen curtains into a dress with empire waist, no closure, inseam pockets, and handkerchief skirt. It is practically zero waste, as I made a circular bag out of the cutoff remnants.

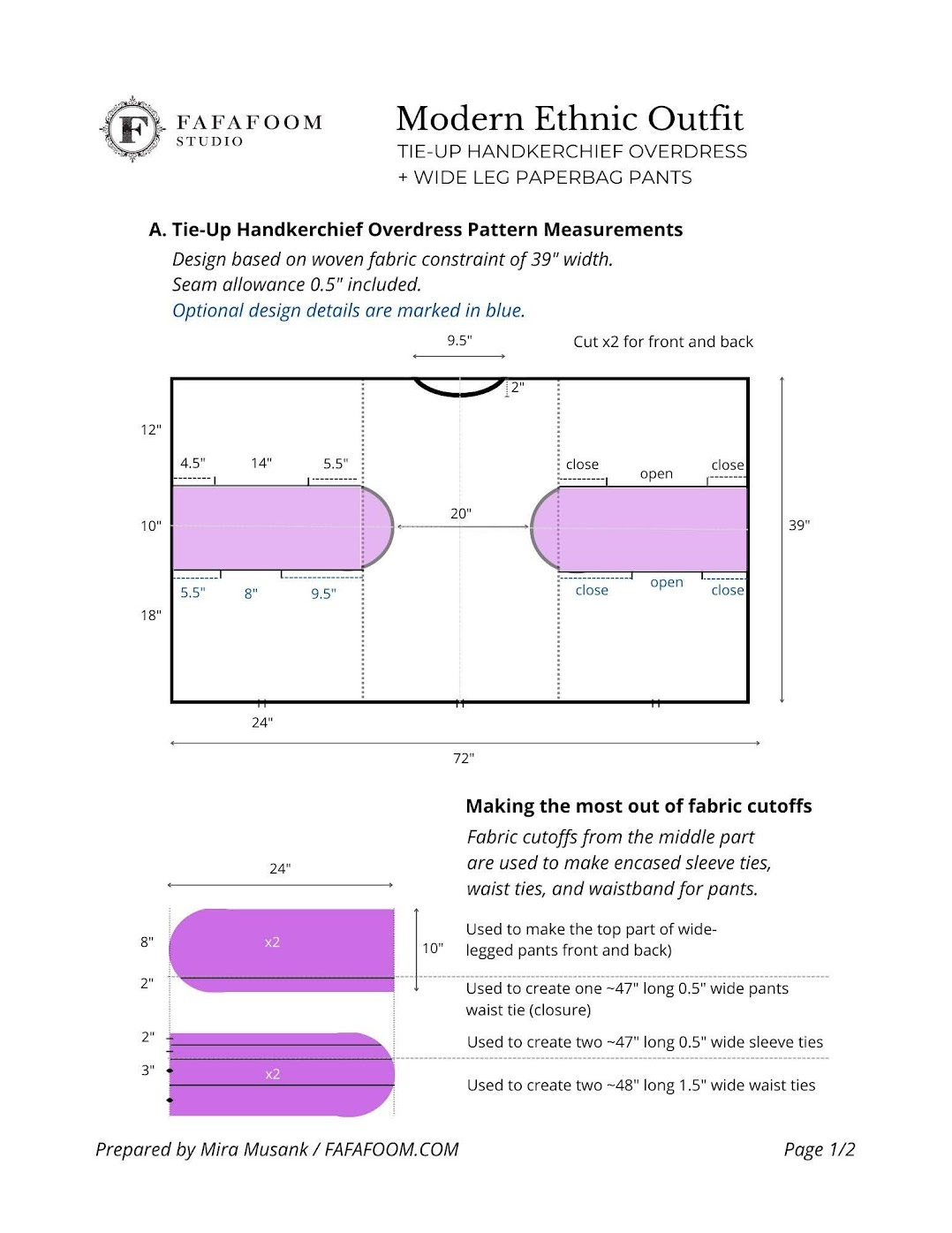

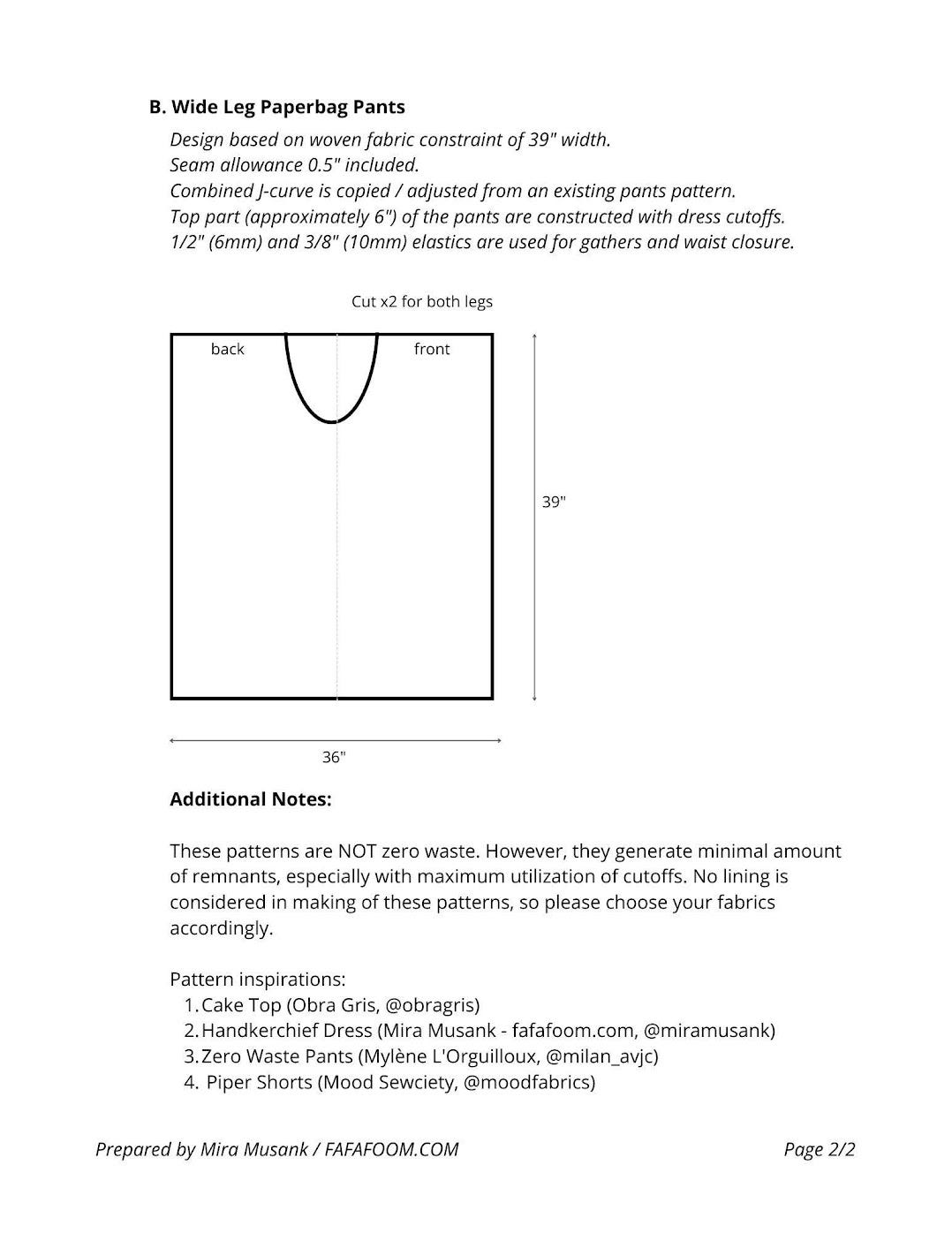

And just last year, I made a zero-waste-inspired ensemble of an overdress and matching pants with an antique ikat fabric. The physical construct of this dress is in my wardrobe, and its digital twin is showcased in my Textile Art Climate Gallery. Happy 1st anniversary, Modern Ethnic outfit!

-

For the Borrowed from the Soil Design Challenge, I will expand on what I have learned so far, and try to really make a zero waste jumpsuit pattern this time. Not 5%, 2%, or even 1% waste. Zero waste pattern making is the goal.

Doing this will involve a shift in my design making process. My current practice is to:

work with whatever remnants you have, in irregular shapes

patchwork them out like puzzle pieces

if there is a shortage of materials to complete the intended design pattern, add more remnants!

On the other hand, to do zero waste design, I need to:

Know the actual width of the fabric (post-wash, to accommodate shrinkage)

Create patterns using the fabric measurements. To make it even more challenging, create 2-3 zero-waste garment patterns in several yards of fabric :)

Cut and sew 100% of the fabrics with no additional materials.

In other words, my usual design practice is independent or codependent with whatever fabric remnants I have on hand because I can always patchwork them. Zero waste design practice will limit that freedom of improvising. Once all of the pattern thinking and making are 100% transferred into the fabric, what’s left is a more efficient cut and sew process.

Does it feel more rigid? Maybe. However, when I’m in the thick of it, I’m sure I will discover exciting new paths to explore. Opportunities like practicing digital pattern making! Doing this will create faster pattern iterations without wasting muslin fabrics to redo physical samples.

For now, though, I’m still warming up my zero waste design mojo…by refashioning a fast fashion item. Well, two items (a top and a dress) from 3.1 Phillip Lim x Target collection in 2013. I deconstructed the top completely and add them to the dress - elongate hemline, alter the armpit holes and sleeves, as well as widen the neckline. My goal is to use the deconstructed top pieces as much as possible, leaving as little waste as possible. Zero waste would be awesome.

As of June 7, 2023, it’s looking very promising! I predict I will end up with less than 5” x 5” area of remnants, but we’ll see! More updates of this project will be shared on my Instagram account.

That’s all for now. I’m excited to closely observe my current practices working with remnants v. working in zero waste design manner. Stay tuned for more updates on this zero waste explorations next month!

Thanks for reading; until next time,

Mira Musank